Who is liable when an AI crashes a car? Image Credit: Shutterstock

With the field of AI developing by leaps and bounds, what legal rights are granted to autonomous non-human beings? In her new series, Giulia Trojano considers the present and future legality of AI. Her investigation began in Part 1 by examining content produced by creative AIs in light of existing and potential copyright protection. Part 2 continued by questioning associations between authorship and personhood, by posing the hypothetical situation of a runway collaboration between creative AIs. In Part 3, Trojano elaborates on the hypothetical: what happens when AI-caused accidents inevitably occur?

Welcome to a world in which a hotel had to lay off half of its AI robots for poor customer service.[1] A world in which Vital, developed by Ageing Analytics UK, sits as a board member of VC firm Deep Knowledge, due to its ability to foretell favourable investments in the field of therapies for age-related syndromes.[2] One in which, in 1981, a Japanese motorcycle factory witnessed an AI kill its human colleague, mistakenly identifying him as a threat to its mission and believing that pushing said human, using its hydraulic arm, into an adjacent operating machine would be the most efficient way to resume its operation.[3] Far from being J.G. Ballard short stories, these are chronicles of our past and present.

The humanist approach to personhood, as touched upon in Part 2, has largely dictated the way in which legislators framed their plans for the liability of AIs. If we are ready to accept that creative AIs such as Young Paint merit legal personhood for their original musical output then this “generally comes with the capacities to own property and be sued”.[4]

Which realities should be morally entitled to legal personality though? Whilst some scholars have argued that “no single principle dictates when the legal system must recognise an entity as a legal person, nor when it must deny legal personality”[5] the issue is highly sensitive and at times revolves around sovereign arbitrariness.[6] Conceiving an electronic person does not derive from the qualities of a natural person, but is the result of legislative options based on moral considerations that seek to update the legal framework to reflect new social realities.[7] This should not appear new as the most common legal fiction of all, the corporate entity, was born out of similar needs to regulate social life and demonstrates that “consciousness” is not a pre-requisite for legal personality.[8]

Yet the European Parliament has not ceased to create a false dichotomy, asking itself how it could possibly contemplate conferring rights and duties on a mere machine, since this idea is closely linked with human morals and claiming that “[creating a new type of person—an electronic person] risks tearing down boundaries between man and machine, blurring lines between the living and the inert […] [and] sends a strong signal which could not only reignite the fear of the artificial beings but also call into question Europe’s humanist foundations”[9] and explicitly stating that “it is essential that the big ethical principles which will come to govern robotics develop in perfect harmony with Europe’s humanist values”.[10]

Equally, from a normative point of view, the possibility of AI causing serious harm is far from remote which is why in February 2017 the European Parliament invited the European Commission to explore and consider “all possible legal solutions […] so that at least the most sophisticated robots could be established as having the status of electronic persons responsible for making good any damage they may cause, and possibly applying electronic personality to cases where robots make autonomous decisions or otherwise interact with 3rd parties independently”.[11]

e-David in his “studio”

Despite the European Parliament referring to ‘fear of the artificial beings’, a recent survey aimed at mapping European attitudes to technological change and its governance noted that whilst many participants voiced concerns about increased automation and its impact on job markets, 1 in 4 Europeans would prefer AI to make important policy decisions concerning the running of their country. In the UK, Germany and the Netherlands the figure was 1 in 3.[12] If, as a result of disillusionment with our current governments and failing democracy, we are ready to place more trust into AIs then understanding the way in which AIs make decisions becomes crucial.

As noted, feeding AIs large quantities of data and being unable to control how the neural network processes it is very much a contemporary challenge. Analysing associated enforceability issues is equally as pressing as recognising and rewarding an AI’s creative efforts and, arguably, should have priority.[13]

In order to discuss such challenges, recall the fashion show once again. The show is hosted in a conference centre built in only 100 days[14], designed by a new AI-led architecture design studio, which employed AI robots to 3D-print concrete landscaping around the museum and others to mould, weld and assemble the main structure with the supervisory assistance of drones to map and conduct site inspections.[15]

AI-generated models

Now, imagine that invitees to the fashion show will be escorted to the venue with self-driving cars (Driver-AI). Passenger A finds himself in a shell he cannot control (physically or remotely), a car which decides, seemingly out of the blue, to speed, despite visible limits on the road, and eventually swerves into the venue, severely hurting Passenger A[16] whilst another AI robot, tasked with greeting guests and ensuring operations run smoothly, calculates that the best solution to restore order after the incident is to crush Passenger A’s body and call for a clean-up.

Gabriel Hallevy, professor and researcher in theories of criminal law, proposes three models for attributing criminal liability in such an incident.[17] Firstly, the AI could be considered as perpetrator-via-another, where the AI programs responsible for operating the self-driving car or determining that a crush-and-clean solution would be most efficient would be held as innocent agents, whilst their software programmers or users (in our case, the firms that employed them specifically for the role) would be the perpetrators. This isn’t unlike models used in cases involving an animal killing a person, where the animal lacks sufficient mental capacity to comprise mens rea—i.e. the knowledge of committing a crime—and it is therefore the animal’s owner who must respond to associated criminal consequences.

Alternatively, the accident could be assessed using the natural-probable-method. In this case part of the AI programme intended for good (in our case, to drive Passenger A safely to the show or to greet guests) is activated inappropriately, such that a fatal crime is committed. Hallevy observes that once again programmers would likely be prosecuted if they knew that a criminal offence was a natural, probable consequence of their program or its application. However, adopting this model would necessarily entail distinguishing between AI’s that ‘know’ they are performing a criminal act (because they were programmed to do so) and those that do not.

Finally, AIs could be held directly liable meaning that actus reus (i.e. the act of committing a crime) and mens rea would be attributed to them. This could function for strict liability offences, where no intent to commit a crime is required, as is the case for our speeding Driver-AI. However, issues could easily arise as defences. Could an AI avail itself of program malfunctioning in the same way a person could avail himself of insanity? Could a virus exculpate the self-driving car? What if it is argued that a Trojan program caused the deadly behaviour, then wiped itself out before the car could be forensically analysed? A jury could be convinced that such a scenario is not beyond reasonable doubt and could therefore find upholding any conviction difficult in practice.[18] Further, who would be responsible for representing either of the AIs in court and, if they were convicted, what type of sentencing would they receive given that traditional punitive sanctions such as jail would be ineffective and likely unavailable?

Whilst useful as a starting point, each of Hallevy’s models ultimately results with the programmer being deemed liable. Understandably, there is a risk that “two kinds of abuse might arise at the expense of human legal rights—humans using robots to insulate themselves from liability and robots themselves unaccountably violating human legal rights”[19] but in cases with distributed liability (as discussed in relation to copyright protection) once again, the search for a human behind the machine may lead to impunity or could be particularly onerous on a particular programmer in the interest of providing the victim’s family with redress.

Temporarily leaving Passenger A behind us, let us now focus on the fashion show itself, and in particular on the clothes which are purchasable in real time and delivered 24 hours later. It emerges that when worn, the metal choker on one of the designs, intended to act as a “mood ring” heats up unpredictably, causing buyers to develop burn marks.

Routinely, were something like this to occur in our daily lives, we would have an action against the product manufacturer for breach of warranty or in tort for negligence.[20] In order to prove negligence on the part of our Balenciaga designer-GAN and its production team, speared by SewBot, Buyer B would need to assert that designer-GAN and team owed her a duty of care, they breached said duty and that breach caused her an injury.

As Gerstner rightly contends, it would be difficult to determine what standard of care (if any) a software system owes to its user (in this case, Balenciaga the fashion house) and suggests that understanding whether the AI, for example merely recommended an actions—such as recommending that the production team buy and use potentially dangerous materials in manufacturing the designs—or took said action by ordering and implementing these in the production stage would inform our position. [21] Balenciaga could also argue that it hired its designer-GAN and team to perform a service and, as a result of the AI-team manufacturing dangerous clothing and not informing the fashion house of its limitations, it suffered an underinsured loss.[22] Meanwhile Buyer B may be left without compensation.

Both scenarios—passenger A’s death and Buyer B’s burns—illustrate limitations affecting both humans and AIs themselves. Reality changes rapidly and whilst a vendor selling an AI-product such as Driver-AI can communicate these limitations, and provide updates to the software system, we risk needing to quantify how often these should be delivered and at what point in time the vendor or programmer will cease to be responsible. The use of licensing bodies issuing ‘health’ certificates for AI systems has been advanced by the US Securities and Exchange Commission in requiring stock market recommender systems to be registered as financial advisors, and classified developers of investment advice programs as investment advisors, for example.[23] The same strategy however might not be applicable in the context of creative AIs, when these are employed for their intuition and thus require a higher degree of unpredictability.

Actress performing with Young Paint

Returning now to Young Paint and e-David, recall that, during the fashion show, e-David’s visuals started resembling David Hockney’s works whilst Young Paint, now working under a different label than Actress’s Werk is producing and playing tracks that sound like Actress’s own.

In the case of e-David, it emerges that programmers trained the AI using Hockney’s work, amongst others, as scraped from Google Images, Instagram and an online version of the catalogue published for the Royal Academy’s exhibition. Despite individual images being protected under copyright, none of the authors or licensors were asked to give consent. E-David was effectively given access to the internet. Programmers had not pointed e-David in the direction of Hockney, rather it seemed to respond to the artist’s pleasing colours on its own accord and, by investigating his work further, assimilated his style.

In the case of Young Paint instead, we know Darren J. Cunningham trained the AI using the music he produces as Actress for a number of years. Warner Music though, after “hiring” Endel[24], decided to continue focusing on AI-produced music and entered into an agreement with Young Paint, using a different distribution deal—this time in Young Paint’s own name.

Fast forward to the hearings and a first court rules that eDavid has breached GDPR and data protection regulations whilst a second rules that Young Paint has infringed Cunningham’s copyright and broke non-compete clauses in its contract with Werk. If neither e-David nor Young Paint have legal personalities, but distributed liability is such that no programmer or stakeholder can be singled out as being responsible. Where does this leave us?

Although motivated by economic factors the European Commission has taken a pragmatic approach and started preparing draft AI ethics guidelines due to be published this month adding that “the Union has high standards in terms of safety and product liability” and that specific proposals need to be adopted as soon as possible so that citizens and businesses can trust the technology their interact with.[25] The proposed ethical guidelines build upon a further paper produced by the European Parliament[26] which contended that basic robo-ethical principles had to be devised to protect humans from such technology. Amongst these we find “protecting humanity against privacy breaches committed by robots” although the paper is quick to add that “the perpetrator of the breach would not be the robot but the person behind the scene”.

On data alone, in January 2019 IBM was under fire because as part of its efforts to reduce bias in facial recognition, it compiled a data set for AI training using around a million photos taken from Flickr without obtaining consent from anyone.[27] The Commission envisages creating a common European Data Space in order to facilitate data sharing between public and private sectors. These would include high-value datasets (such as medical health records) that can be used to train AIs but that are crucially anonymised and based on data donorship by patients.[28] Similar guidelines might prevent AIs such as e-David from being trained on unlicensed images in the future.

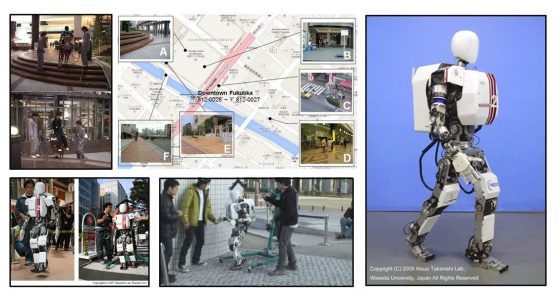

Special zone in Fukuoka, Japan, where bipedal humanoid robots are being tested on public roads

Inspired by Japan’s “testing zones” the Commission also tackled issues arising from product liability and driverless cars (eg Driver-AI) by recommending the development of a limited number of AI testing facilities to experiment with autonomous shipping, driving and the creation of data spaces. The sites could include a “regulatory sandbox” where law would provide authorities with sufficient leeway for the duration of the sandbox, thereby allowing legal frameworks to adapt once the best solution to arising problems is found in testing.[29] These are due to be created in 2020 whilst Member States are currently encouraged to create one-stop-shops for companies developing AI applications to discuss their specific needs.

These are important steps forward but the question of enforceability and accountability of an independent-thinking AI remains in many ways unanswered. How will Buyer B be compensated for burn marks caused by the metal choker? How will Cunningham and Werk be compensated for Young Paint’s breaches? Lawmakers face difficulties where designers can exempt themselves from liability because they have effectively complied with all necessary steps but persons still suffer damages from the unpredictable, evolving behaviour of an AI.

One way to resolve the conundrum is to create specific insurance schemes. Designers and programmers of an AI would subscribe to an insurance, meaning that the insurance premium would pay for damages.[30] If, on the other hand the designer/programmer were negligent, then they would be personally liable to compensate Buyer B.

The solution was supported by the European Parliament in its report to the Commission[31], which suggested that all parties contribute in varying proportions to the funds (designers, users, owners). The viability of the scheme has to be considered further as it would be far easier to place an insurance burden on the original designer and then pass the cost onto the buyer upon purchase.[32]

Again, whilst an insurance scheme does not address in the immediate whether AIs should have full legal personhood, it does advance the discourse and certainly seems more applicable to AIs than punitive enforcement measures.

As 2019 progresses and the European Commission publishes further guidance on its plans for “ethical AI” Young Paint and e-David may find themselves in the near future with rights to hold copyright in their musical production and visual works but also liable to any claims or lawsuits for breach of the same.

The present three-part investigation cannot hope to provide answers for legal solutions that govern relations with and between Creative AIs but the time is ripe to test these and make our legal systems flexible enough to accommodate our protagonists.

[1] See the Verge: https://www.theverge.com/2019/1/15/18184198/japans-robot-hotel-lay-off-work-for-humans

[2] U. Pagallo, Vital, Sophia and Co. – Quest for legal personhood of robots

[3] J.K.C. Kingston, AI and Legal Liability; see also: https://www.beasleyallen.com/news/work-robot-blamed-michigan-womans-death/ and https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2017/03/14/rogue-factory-robot-blamed-death-human-colleague/

[4] L.B. Solum, “Legal Personhood for Artificial Intelligence” (1992) 70 North Caroline Law Review

[5] T.Allen and R. Widdison, “Can Computers Make Contracts?” (1996) 9 Harvard Journal of Law & Technology

[6] See for example New Zealand granting legal personhood to rivers, or Saudi Arabia granting legal personhood to Sofia the robot

[7] F M Alexandre, The Legal Status of Artificially Intelligent Robots: Personhood, Taxation and Control (2017)

[8] Ibid. (F M Alexandre)

[9] European Civil Law Rules in Robotics, European Parliament (2016). The EP continues by adding that “assigning person status to a non-living, non-conscious entity would therefore be an error since, in the end, humankind would likely be demoted to the rank of machine. Robots should serve humanity and should have no other role, except in the realm of science fiction”.

[10] European Civil Law Rules in Robotics, European Parliament (2016)

[11] s 59f of Feb 2017 European Parliament invitation to Commission

[12] See https://www.ie.edu/cgc/research/tech-opinion-poll-2019/

[13] See U. Pagallo’s thesis in Vital, Sophia and Co. – Quest for legal personhood of robots.

[14] See: Archi-Union Architects built Venue B to host an AI conference. Read more on https://www.dezeen.com/2018/11/23/archi-union-venue-b-conference-centre-cyborg-fabrication-shanghai/

[15] See Dezeen: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/02/20/robot-science-museum-melike-altinisik-architects-maa-seoul/

[16] See the Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/19/uber-self-driving-car-kills-woman-arizona-tempe and https://qz.com/1558033/a-software-malfunction-is-injuring-lime-riders-around-the-world/

[17] See G. Hallevy, The Criminal Liability of Artificial Intelligence entities (15 February 2010) https://www.technologyreview.com/s/610459/when-an-ai-finally-kills-someone-who-will-be-responsible/

[18] For examples of UK cases invoking the Trojan defence see https://www.theregister.co.uk/2004/01/20/the_giant_wooden_horse_did/. See also the US-based case of Eugene Pitts (2003). Prosecution claimed that Pitts underreported more than $630,000 in income by filing fraudulent returns. Pitts argued that a virus had modified his files and this had resulted in his firm’s underreporting. Although prosecutors pointed out that the alleged virus had not affected tax returns of the firm’s customers which were prepared on the same machine, the jury acquitted Pitts of all nine charges.

[19] Bryson JJ; Diamantis, M.E; Grant T.D. Of, for and by the People: The Legal Lacuna of Synthetic Persons. Artif. Intell. Law 2017, 23, 273-291

[20] Under the Consumer Protection Act 1987, for instance

[21]Gerstner M.E.: Comment, Liability Issues with Artificial Intelligence Software, 33 Santa Clara L. Rev. 239. http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol33/iss1/7 (1993)

[22] A school district brought an action of this kind in negligence against a statistic bureau that allegedly provided inaccurate calculations on the value of the school that burnt down, so the school suffered an underinsured loss. The statistic bureau’s duty was to provide information with reasonable care and the court considered factors such as the undesirability of requiring an innocent party to bear the burden of another’s professional mistake. See Independent School District No. 454 v. Statistical Tabulating Corp 359 F. Supp. 1095. N.D.Ill. (1973).

[23] Mykytyn K., Mykytyn P.P., Lunce S.: Expert identification and selection: Legal liability concerns and directions. AI & Society, 7, 3, pp. 225-237 (1993)

[24] Warner Music signed a deal with the programmers behind Endel, an AI that produces music often used for background playlists. Despite press reports, Endel was not a signatory to the contract with Warner. Rather, Warner Music a 50/50 distribution deal – ie 50% of royalties will go to the programmers – covering a total of 20 albums released throughout 2019. See http://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2019/03/warner-music-signs-distribution-deal.html

[25] European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, EU Council, EESC and Committee of Regions, AI for Europe (25 April 2018)

[26] Draft Report with Recommendations to the Commission on Civil Law Rules in Robotics, European Parliament (2016)

[27] See Technology Review: https://www.technologyreview.com/the-download/613118/peoples-online-photos-are-being-used-without-consent-to-train-face-recognition/

[28] Coordinated Plan on the Development and Use of AI Made in Europe – Annex to the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament (December 2018)

[29] ibid.

[30] See fn. 7

[31] See fn. 26

[32] See fn. 7

—

Giulia Trojano works for international law firm Withers as an associate, with an affinity for art law. Currently based in Milan, she regularly writes for FAD Magazine and is assistant editor of the recently launched broadsheet, Art of Conversation. She is particularly interested in advancing legal and political discourse through a close study of contemporary and experimental art forms. Giulia graduated from the LSE with an LLB in Law and prior to that lived in Rome and Vienna.