Senga Nengudi, RSVP, 1977 (via Senga Nengudi)

The 1960s and 70s was an era in which art was being taken in radical new directions. This period also saw a sea-change in social structure and the position of women. As social mores surrounding sexuality began to relax in the early 1960s, sexual explicitness became an acknowledged source and subject for culture. Sex became something to be represented, scrutinised and celebrated in art.

Women artists such as Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, Rebecca Horn, Hannah Wilke and Lynda Benglis used expanding definitions of both art and sexuality around this time in order to incorporate materials that were new to art into their practice, such as latex, cloth, vinyl, polyurethane foam, fibreglass, neon and chewing gum. The non-traditional form and presentation of these works is symptomatic of the influx into art of historically non-artistic materials, which many of these artists used in order to explore the erotic.

One of the most significant social changes of the 1960s was the way in which women began to lay claim to their sexuality, sometimes in challenging or aggressive ways. Feminism, in both art and art criticism, was vital to the development of art in this period. New materials and art forms provided women with a platform for the expression of their personal experiences as women and of the general condition of womanhood.

However, feminism was not a strict doctrine adhered to by all artists who expressed concern with women’s lot. On the contrary, it constituted (and still constitutes) a highly divergent spectrum of opinions, theories and aesthetics. As Cornelia Butler maintains in her essay to accompany the exhibition of feminist artwork, WACK!, ‘whereas art movements traditionally defined by charismatic individuals tended to be explicated and debated through manifestos and other writings, feminism is a relatively open-ended system that has, through its history of engagement with visual art, sustained an unprecedented degree of internal critique and contained wildly divergent political ideologies and practices.'[i]

Even women artists with closely aligned practices don’t always express the same points of view concerning women, the erotic, and what a ‘feminist’ art practice might constitute. For example, while many feminists condemned pornography and the objectification of the female body, Hannah Wilke took a more nuanced view. She argued that within traditional attitudes towards sexuality, “the pride, power, and pleasure of one’s own sexual being threaten cultural achievement, unless it can be made into a commodity that has economic and social utility. Generating a pornographic attitude toward sexuality creates a money market that promotes and supports financial success and a way of life for both men and women.”[ii] In order to counteract this, she claims, ‘women must take control of and have pride in the sensuality of their own bodies and create a sexuality in their own terms, without deferring to the concepts degenerated by culture.’

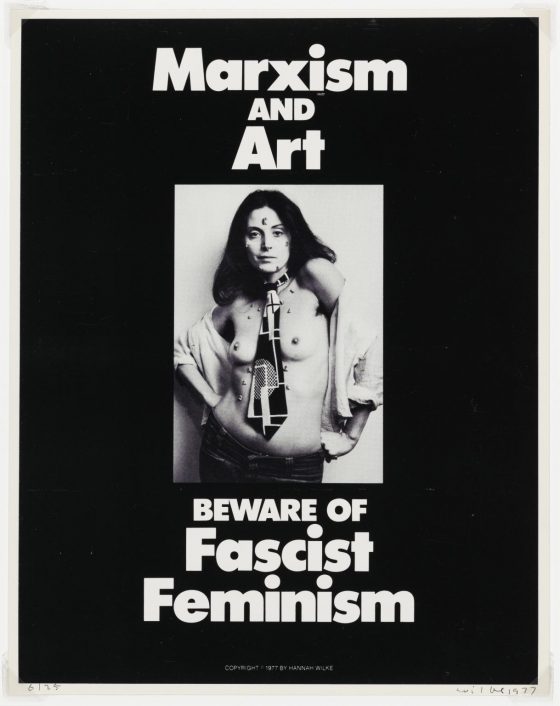

Hannah Wilke, Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism, 1977 (via Tate)

Wilke achieves this in her practice through the presentation of her own nude body; in Marxism and Art (1977) she places on her skin labia-shaped pieces of chewing gum which also resemble tiny wounds, hinting erotically at both pleasure and pain within the female condition. In both Marxism and Art and her text on ‘visual prejudice’, she also warns us to ‘beware’ or ‘resist the coercion’ of a ‘fascist feminism’ which dictates how women should look in a way that is, in Wilke’s view, as harmful as the patriarchal system it rejects. Marxism and Art was created in response to criticism from other ‘feminist’ artists and critics, who argued that Wilke’s self-promotion of her own nude and traditionally attractive body served only to re-fetishise the female body and to reinforce the ‘pornographic attitude’ of the gendered gaze.

Significantly, much feminist art did not constitute a simple replacement of men with women, or of phallic imagery with labial imagery. This is evident in the ambivalently gendered work of many of these artists, including Hesse, Benglis and Bourgeois. Furthermore, many women artists made work which was both phallic and explicit. In 1973, Anita Steckel founded the Fight Censorship group, made up of women artists, including Wilke and Bourgeois, who objected to being censored for including sexually explicit images in their work. A press release by Steckel unequivocally states that ‘if the erect penis is not “wholesome” enough to go into museums – it should not be considered “wholesome” enough to go into women.'[iii]

Central to this debate is Lynda Benglis’s infamous Artforum advertisement of 1974. Benglis purchased advertising space in the eminent magazine’s pages, showing a photograph of herself oiled up, wearing nothing but sunglasses and masturbating with a large double-ended dildo. The photograph remains shocking in its theatrical explicitness and the controversy which arose in its wake remains unresolved. It is so unsettling, as critic Richard Meyer points out, because of ‘its refusal to fall comfortably into either a feminist critique of pornography or a pornographic critique of feminism.'[iv] The viewer is forced to ask whether Benglis is presenting herself as a self-sufficient woman, flaunting her naked and sexual body in an expression of extreme womanhood. Or, with her short hair and small breasts, does she represent a hermaphrodite or androgyne, laying claim to an unnaturally large phallus?

It’s also worth pointing out that many artists who are explicit in their feminism are also simultaneously working within other discourses. For example, the African-American artist Senga Nengudi (born Sue Irons), whose work was featured in this year’s Venice Biennale, creates performances and sculptural works using women’s nylon hosiery. Her message is certainly an explicitly feminist one, but as an artist she is equally concerned with racial issues.

The work of these talented female artists is testament to the variety of art being produced during the sexual revolution, and the fact that this divergence was in part a result of the possibilities opened up by the influx of new or non-traditional materials into art. While feminism may have been a banner under which many of these artists united, they had very different ideas about what it meant, something that holds true of the movement today.

—

[i] Cornelia Butler, WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Cornelia Butler (Cambridge, Mass., 2007) p.15

[ii] Hannah Wilke, ‘Visual Prejudice’, 1980

[iii] Anita Steckel, quoted in Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Cornelia Butler (Cambridge, Mass., 2007) p.366

[iv] Richard Meyer, ‘Bone of Contention’, Artforum, November 2004, 73-74, p.249